Nathan and Sarah are part of the Ettenger branch of the family tree. My relationship to Nathan and Sarah and the preceding and subsequent generations, runs as follows:

- Thomas Watson (1630-1699) m. Jannat Feddell (1630-1699)

- Thomas Watson (1651-1738) m. Rebecca Marke (1663-1742)

- Nathan Watson (1693-1737) m. Sarah Biles (1693-1737)

- Thomas Watson (1726-1780) m. Elizabeth Horner (1728-1786)

- Theodosia Watson (1760-1825) m. John Ettenger (1735-1822)

- John Ettenger (1778-1854) m. Sarah Ann Scott (1781–1870)

- George Ettenger (1819-1890) m. Mary Ann South (1822–1882)

- Harrison South Ettenger (1845-1922) m. Mary Ann Mannington (1846–1909)

- George W Ettenger (1866-1930) m. Mary Elizabeth Balderston (1870–1956)

- Marguerite Ettenger (1899-1988) m. Alfred Leon Moser (1899–1975)

- George Louis Moser (1922-2006) m. Lorraine Ether Harper (1923–2016)

- Moi

Nathan Watson was born on 24-Jan-1693, in Strawberry How, Parish of Cockermouth, in Cumbria in the far northwest of England along the border with Scotland. He was the son of Thomas Watson (1651–1738) and Rebecca Marke (1663–1742).

Nathan arrived in America in 1702, at approximately the age of 9, along with his father, mother, and siblings.

Thomas Watson, of Strawberry How, parish of Cockermouth, county Cumberland, England, came with his wife, Rebecca (Mark) Watson, and children to America in 1702, and settled on a farm of 357 acres, near Oxford valley; a part of which tract is now owned by J. Harvey Satterthwaite, and on which is the old stone graveyard, known then and always since as the Watson graveyard. The children that came over with them were: Mary, who married William Paxson; Nathan, who married Sarah Biles; Amos, who married Mary Hillborn; and Mark, who married Ann Sotcher. Two others, born in America, were: John, born in 1703, who married Ruth Blakey, and Joseph, born in 1705. They were members of the Society of Friends, and their certificate was read and approved in Falls meeting, 3d month, 1702. Thomas Watson was a justice of the peace for many years, perhaps until his death (in 1738), and a prominent man of that time. (History of Bucks County, Pennsylvania: Including an Account of Its Original Exploration by J. H. Battle January 1, 1887, p934)

In the late 17th Century the voyage from England to the colony was long and perilous. The following is a description of what the trip of William Penn would have been like, only three years later.

August 30 to October 27/28, 1682

In August of 1682, the ship Welcome’s trip from Deal, England to Pennsylvania meant a hazardous and, at best, unpleasant voyage of 57/58 days on this very small wooden ship.

The “Welcome”, that carried William Penn to his new colony, was an average size ship for that time. She was likely around 120 feet in length, 24 feet wide and weighed 300 tons. Robert Greenway was her Commander, and she was manned by a crew of about 36. She carried 100 passengers, mostly Friends, from Sussex, England.

When they left London, they could have no idea how long they would be on board the ship, as these ships were “slow sailers”. Although they could go as fast as ten miles per hour when there was a fair wind and a smooth sea, they rarely maintained this speed. The length of the voyage might vary from 49 to 128 days. Sometimes ships that left London at the same time might arrive in America as much as eight or nine weeks apart.

Conditions on the Welcome were likely far from ideal, even for those times. The ship was over-crowded with passengers, and private cabins were available only to the ship’s captain and perhaps William Penn. All the others slept on the floor on the deck below the main deck. There was very little light or air. During the rains and rough seas water would pour in through cracks and joints, drenching the passengers and their belongings below. There were no bathrooms on board. If they wanted to wash, they had to wash in salty water from the sea. Most likely they may have worn the same clothes for the entire voyage.

Although, from time to time, fresh fish or turtles might be caught if weather permitted, meals usually consisted of “salt horse” (salted beef, pork, or fish) and “hardtack” (hard, dry biscuits). There were dried peas and beans, cheese, and butter. Weather permitting; food was cooked over charcoal fires in metal boxes called braziers. But it was often too dangerous to have a fire and so the food was eaten cold.

Food became infested with bugs, the biscuits got too hard to eat, the cheese got moldy, butter turned rancid and even the beer began to go sour by the end of the voyage. Even though a large amount of water would have been taken on board, after standing in barrels for a while, it was neither pleasant nor safe to drink. Everyone, even the children, drank beer instead.

Storms were a great danger, and the Atlantic had many, especially in the fall and winter when the “Welcome” sailed. The tossing and rolling of this small ship, in even a minor storm, caused most of the passengers, many of whom had never been on a ship before, to become seasick. There was the ever-present fear that a major storm could easily capsize a ship of this size or cause it to break apart.

Sickness, other than seasickness, was also a major problem. Even a minor illness could quickly spread among passengers and crew alike. Serious illnesses, often called “ship’s fever” (smallpox), killed 31 of the passengers on the Welcome’s crossing. The Captain was forced to put into Little Egg Harbor in New Jersey in order to allow for the “fever” to run its course. They were still pretty fortunate as on some voyages as many as half the passengers died before they reached their final destination.

The prospect of this long, dangerous, and unpleasant voyage was not made more tolerable by the conditions passengers faced upon arrival in the new colony. They were arriving in the early winter and would not be able to build their permanent homes until the next spring.

Still they chose to face these hardships and exhibited the faith and spirit that embodied the birth of their new home, Pennsylvania.

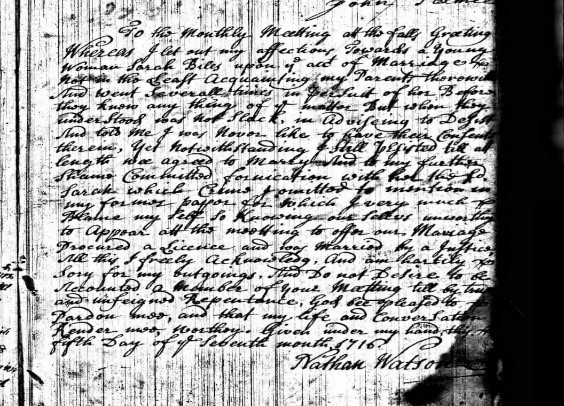

I have yet to uncover any records of Nathan’s early years, but in July of 1716, at age 23, Nathan took the extraordinary step of defying his parents by eloping and withdrawing from the Falls Meeting of the Society of Friends (Quakers) due to opposition by his parents to his marriage to Sarah Biles. His letter to the Meeting reads:

To the Monthly Meeting at the Falls Granting

Whereas I let out my affections towards a young woman Sarah Biles upon [????] act of marriage. Not in the least acquainting my parents therewith and went several times in pursuit of her before they knew anything of the matter. But when they understood was not slack in advising to desist and told me I was never like to have their consents therein. Yet notwithstanding I still persisted till at length we agreed to marry and to my further shame committed fornication with her [????] Sarah which crime I omitted to mention in my former paper for which I very much blame myself. So knowing our selves unworthy to appear at this meeting to offer our marriage, procured a license and was married by a justice. All this I freely acknowledge and am heartily sorry for my outgoings and do not desire to be accounted a member of your meeting till by true and unfeigned repentance, God be pleased to pardon me and that my life and conversation render me worthy. Given under my hand this fifth day of the seventh month 1716.

Nathan Watson

I do not know for certain why Nathan’s parents opposed the marriage but since Sarah’s father Charles had died twenty years earlier, when Sarah was just three, she may well have been dower-less, which would have been ample reason for the Watsons to oppose the union.

Quaker couples in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries had to undergo a series of moral tests and the scrutiny of the Quaker society prior to their marriage. Not only did Quakers need consent for marriage from both sets of parents, they sought the permission of the whole Quaker community as well.

Quaker customs encouraged marriage within their own population and often disowned or banished those who decided to marry outside of the faith. The culture of the colonial Quaker society aimed to maintain a tight knit spiritual community, so they encouraged Quaker matches in the hopes of growing that community. This meant they needed to have a large population of diverse families, since they also prohibited marriages between blood relations. This included cousins up to the fourth degree removed.

They also forbid widowed Quakers from marrying their spouses’ relatives. The relatives of their deceased spouse were considered to be an extension of their family and would have violated the colonial marriage customs. These restrictions were a larger issue than they might be today, since in the 17th Century, death rates were high, and individuals often had multiple marriages during their lifetime.

When a Quaker couple first proposed marriage, they began by seeking the approval of their parents (even if they were mature adults). Their written consent was needed if a couple was to proceed with the marriage. After receiving a blessing from both sets of parents, the couple presented their proposal to the entire community at the Quakers’ monthly religious meetings

Sarah Biles (1693–1737) had been born in Bristol, Bucks County, and was the daughter of Charles Biles (1665–1696) of Dorchester, Dorset, and Sarah Wood (1670–1731) of Attercliffe, Sheffield, Yorkshire.

The Biles families settled in Bucks County, where they had large land holdings. William and Charles were among the original settlers of Falls Township, the “mother township” of Bucks County. They purchased land from Sir Edmund Andros, who represented the Duke of York. The Biles were Quakers, active in the Friends Society, and were signers of Penn’s Great Charter, along with William Penn himself, in 1683.

From Phineas Pemberton‘s List of Arrivals:

“William Biles, vile monger [a seller of glass products], and Johannah, his wife, arrived in Delaware River in the Elizabeth and Sarah of Weymouth, the 4th month [June], 4th day, 1679. Besides his wife and five children, he brought with him two young servants: Edward Hancock to serve eight years and Elizabeth Petty to serve seven years, afterward each to receive 40 acres. They came to America from All Saints Parish, Dorchester, Dorset Co., England.” Charles Biles, brother of William, also accompanied the family. Charles was a partner in some real estate purchased in Pennsylvania.”

A 1690 map by Thomas Holmes, representing property ownership as of 1681, shows William Biles with two tracts of land that fronted the [Delaware] river and another that he and his brother, Charles, owned jointly.

William Biles, my 9th great-uncle, was a prominent man, and is famous in Pennsylvania history. He was a judge, attorney, legislator, sheriff, land speculator, merchant, and a prominent Quaker minister. He was a Justice of the first Provincial (Supreme) Court which was convened as early as 1681, a member of the Pennsylvania Provincial Council from 1683 to 1700, and of the Legislature from 1686 to 1708. He owned large tracts of land in Pennsylvania and New Jersey (including more than 50,000 acres in what is now Salem County, New Jersey.

His brother Charles, my 8th great grand-father, was not nearly so renowned. Perhaps this is because Charles, the younger brother to William by 21 years, was only fourteen when he arrived in the colony in 1679 and he died only 16 years later, at the age of thirty.

His minority upon arrival might explain why Charles’ original land holding was owned jointly with William. William, on the other hand, was an adult of thirty-five years when he arrived, and he lived to the age of sixty-five.

It would appear as if Nathan Watson practiced as a lawyer. An entry on page 251 of J. H. Battle’s, “History of Bucks County,” states:

In spite of Quaker opposition, the lawyers had at this time gained a secure foothold in the Bucks county courts, and there were now oyers, imparlances, continuances, etc., in approved form. Henceforth, technicalities were to be resorted to and insisted upon in spite of impotent protests. In 1701, the courts had been authorized to make their own rules of practice, and in the year succeeding the appointment of the deputy attorney-general appears the first court rule. It is found under date of December 11, 1709, and provides “that where the defendant imparles, he shall plead at least ten days before the second court in order that a venire may issue for tryal.” The admission of lawyers to the Philadelphia courts was authorized by law in 1710, and five years later this provision was extended to all the courts of the province. Any complete list of the attorneys admitted at this time is impossible, but the “appearance docket” now on file in the prothonotary’s office gives the names of those who had cases in court from 1727. From that date to 1734 the lawyers whose names appear most frequently were Joseph Growden, Andrew Hamilton, Thomas Biles, Nathan Watson, John Emerson, William Pierce, G. H. Sherwood, John Baker, Isaac Pennington, Thomas Bowes, William Fry, and John Grohock. Most of these men were residents of Bucks county, though such of them as gained distinction in the profession practiced much in Philadelphia.

The same source also has Nathan as a “Borough Officer” in 1730 and 1731 for, I believe, Bristol Borough.

The Genealogical Society of Pennsylvania also has Bucks County Coroners Records for the years 1710-1729. Among the records preserved in the archives is a series of inquisitions held by the county coroners, pursuant to their investigations of sudden, violent, or suspicious deaths. Two of these records mention Nathan Watson. The first:

9 May 1722.

Subject: James Padwick, “there being Burnt or scorched to Death.”

Place: “at Bristol’

Report: “on the 9th day of may afforsaid about one a Clock in the morning, in the house of one Robert Pritchet in Bed Being, and the said house through some accident taking ffire the said house was Burnt and then and there the said James Padwick Immediately Dyed.”

Jury: Nathan Watson, Samuel Bunting, James Watson, John Brown, Richard Mountain, Benj. Harris, George Clough, Henry Mitchell, Tho. Marriott, Thomas Pilling, John Large, David Palmer.

Coroner: William Atkinson.

The occasion of the above death was a major fire that took place at Bristol during the spring fair. See Terry A. McNealy, “Bristol’s Great Fire of 1722”, Mercer Mosaic (Journal of the Bucks Co. Historical Society), vol. 4, no. 2 (1987), 45.

and the second:

31 May 1722.

Subject: William Blow, “Late of Trenton in the County of Hunterdon within the western Division of Nova Ceserea Waterman.”

Place: “on the shore near the Plantation of one William Dowdney in the township of Bristoll.”

Report: “on the 11th day of November Last Between the hours of six and ten a Clock in the evening the said William Blow sailing in a Boat Between Bristoll and Trenton afforsd was in a storm accidentally Cast over-board and Drowned.”

Jury: Richard Mountain, Nathan Watson, Tho. Clifford, Willm. Watson, Benj. Harris, David Palmer, George Clough, Ana. Hall, Peter Webster, Henry Tomlinson, Thomas Pilling, James Moon.

Coroner: Wm. Atkinson,

Nathan and Sarah Watson had five children:

- Rebecca, b.1717;

- Margaret, b.1719;

- Isaac, b.1722;

- Sarah, b.1723; and

- Thomas, b.1726, who married Elizabeth Horner and became my 6th great-grandfather .

Both Nathan and Sarah died in 1737 at the age of forty-four, and while I have not uncovered documentary evidence of the causes of their deaths, their ages and the coincident year of their deaths leads me to conclude that they likely died of illness, which would have been a common occurrence at the time.

“..infectious disease claimed lives daily, and epidemics occurred every year [in the Philadelphia area]. The region faced threats from three major sources of infection: contamination of food and water with typhoid and other intestinal pathogens; airborne pathogens such as smallpox and measles; and insect vectors carrying diseases, especially malaria and yellow fever, though dengue also circulated..”