In September 1854 there was no such thing as a unified Germany. There were Prussia, Bavaria, Saxony, and a handful of Kingdoms, Duchies, Principalities, and Palatinates.

Nearly one million Germans immigrated to America in the 1850s, one of the peak periods of German immigration. In 1854 alone, 215,000 Germans arrived in this country. An interesting discussion of the reasons behind the large German exodus can be found in The Causes of the German Emigration to America 1848-1854. (Jesse June Kile – 1912)

The Crimean War, which had begun the previous October, and saw England, France, The Turkish Ottoman Empire, and Sardinia pitted against the Russian Empire, was on the precipice of the Battle of Alma (Sept 20, 1854), and The Charge of the Light Brigade (October 1854).

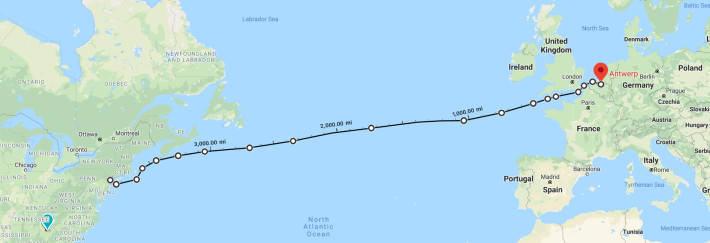

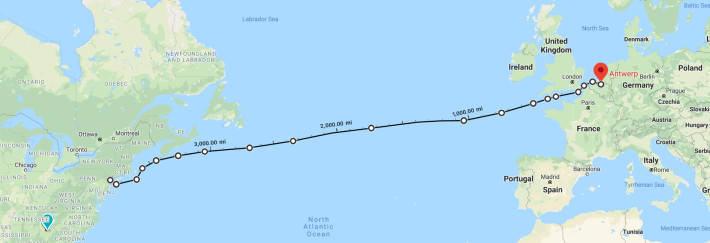

Against this backdrop, in late summer 1854, Franz Phillip, his wife Catherine, and four of their nine children made their way from their home in the village of Muhl, in the Trier-Saarburg region of the Rhineland Palatinate, located roughly 80km due east of Luxembourg, to Antwerp, Belgium, a trip of more than 300km.

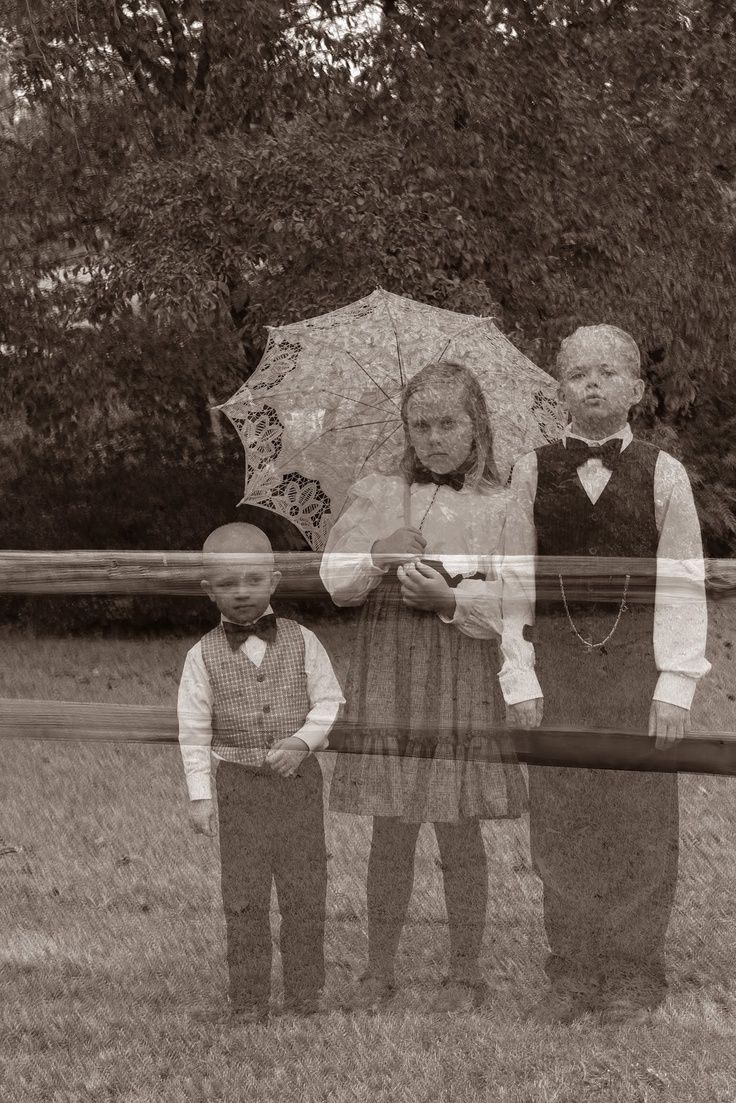

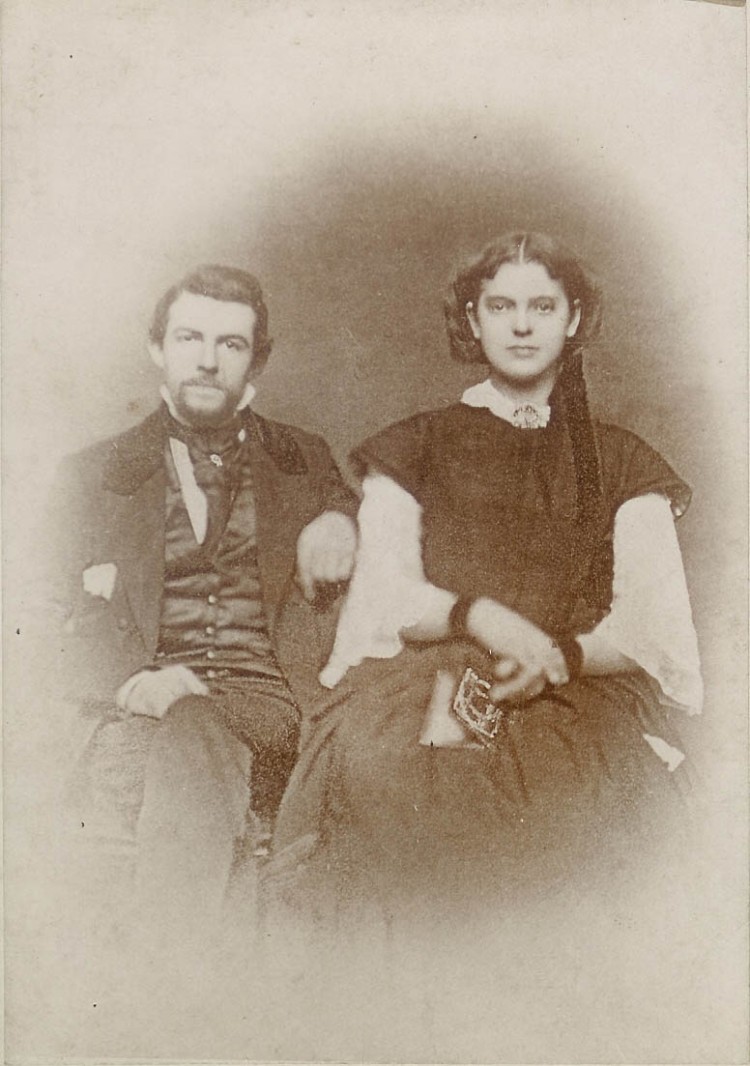

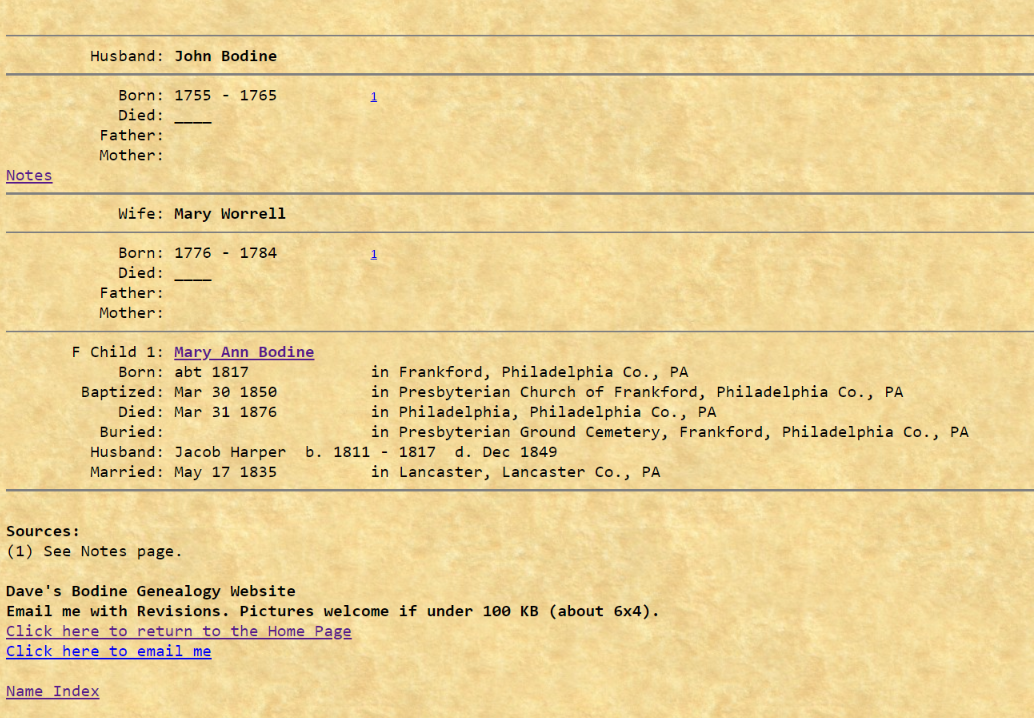

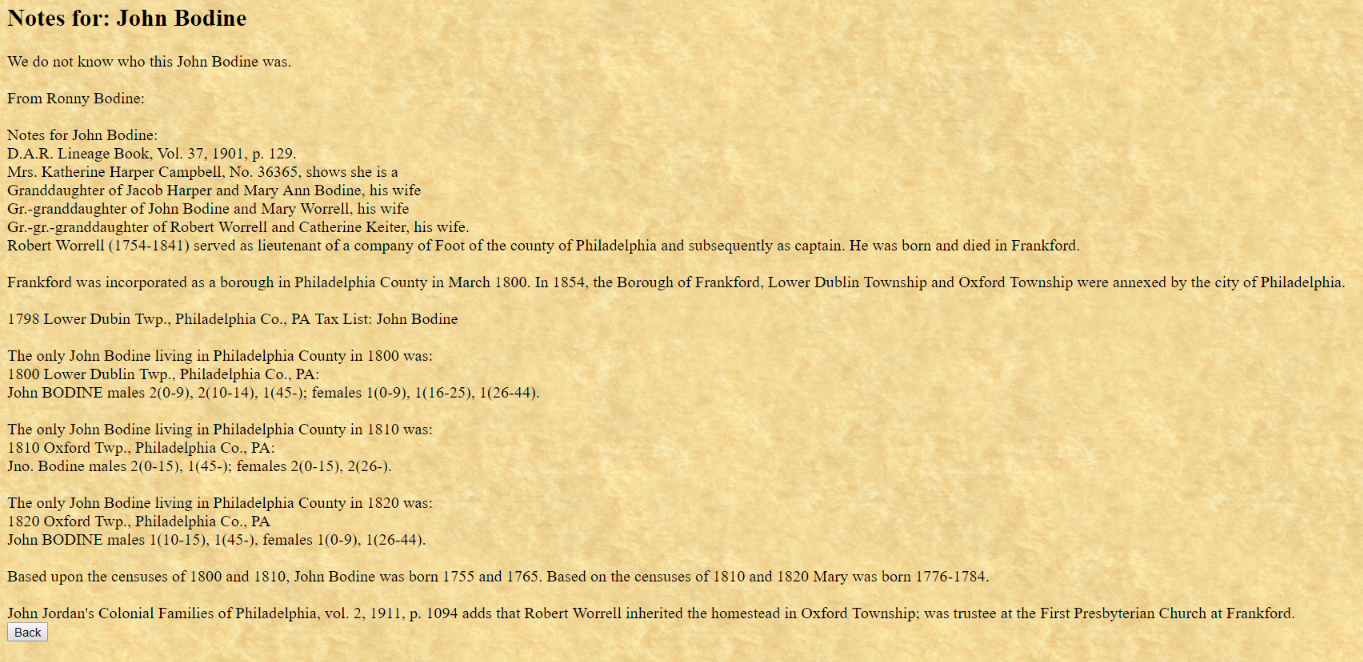

Franz and Catherine are two of my maternal third great-grandparents. Their son, [Karl] Jacob Phillips, who accompanied them on the journey, is a maternal second great grandfather. Franz was fifty-one years old in September 1854. Catherine was fifty, and Jacob was twenty-one.

At roughly the same time, approximately 200km to the north, a man named Heinrich Johann departed Dusseldorf and made his way to Antwerp via Aachen by rail, a trip of roughly 220km. It seems likely to me that the Phillips also journeyed to Antwerp via Aachen as that was a main rail hub at the time. It is even possible that they crossed paths with Herr Johann at the train station.

The Phillips family and Herr Johann were all to be passengers on the English barque Hiero, bound for New York, a trip of approximately 4,000 nautical miles.

A barque (also spelled bark) was a three-masted vessel having square sails on the forward two masts and a single fore-and-aft sail on the rear (mizzen) mast. This rig was easier to handle than a three-masted ship having square sails on all three masts. Averaging about 325 tons, barques, like fully square sailed ships, had a large crew of up to thirty-six sailors.

According to the Herr Johann’s journal, the Hiero was 140 feet in length and 26 feet in breadth.

If you haven’t physically been aboard a sailing vessel of the period, it is difficult to comprehend just how small a boat this is. By way of comparison, if you laid three semi-trailers end-to-end, that is the approximate length of the Hiero. Another comparison is that 140 feet is just less than 1.5 times the distance from home plate to first base in a Major League Baseball park.

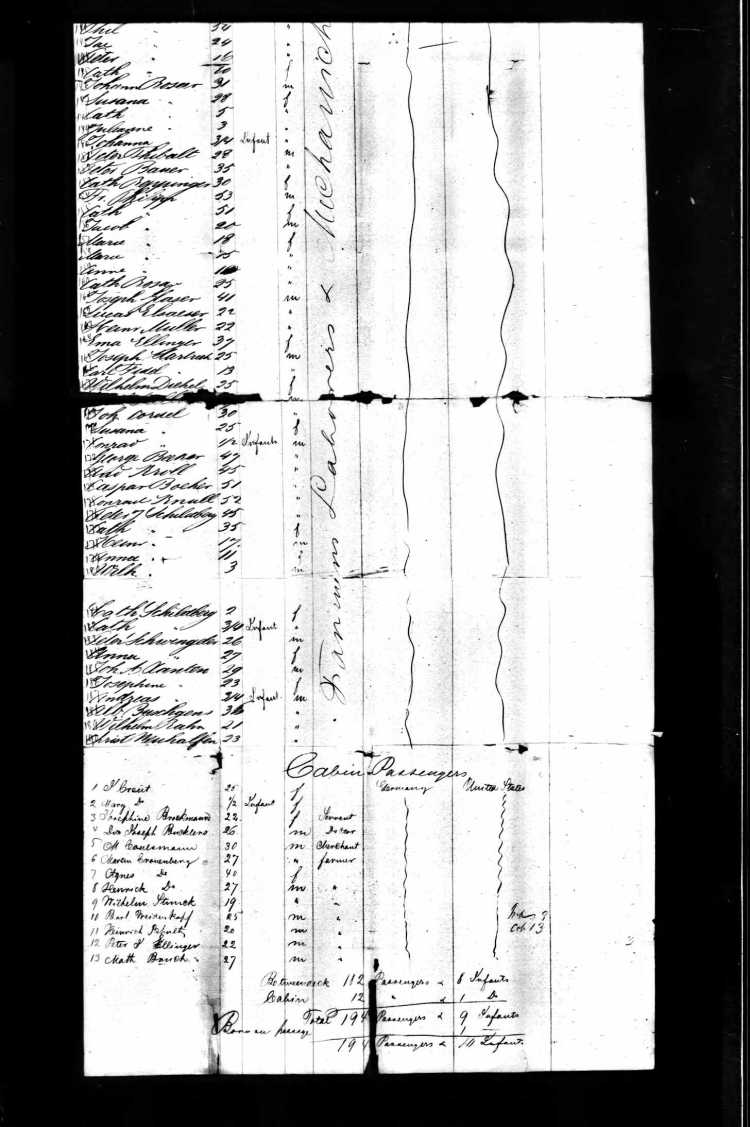

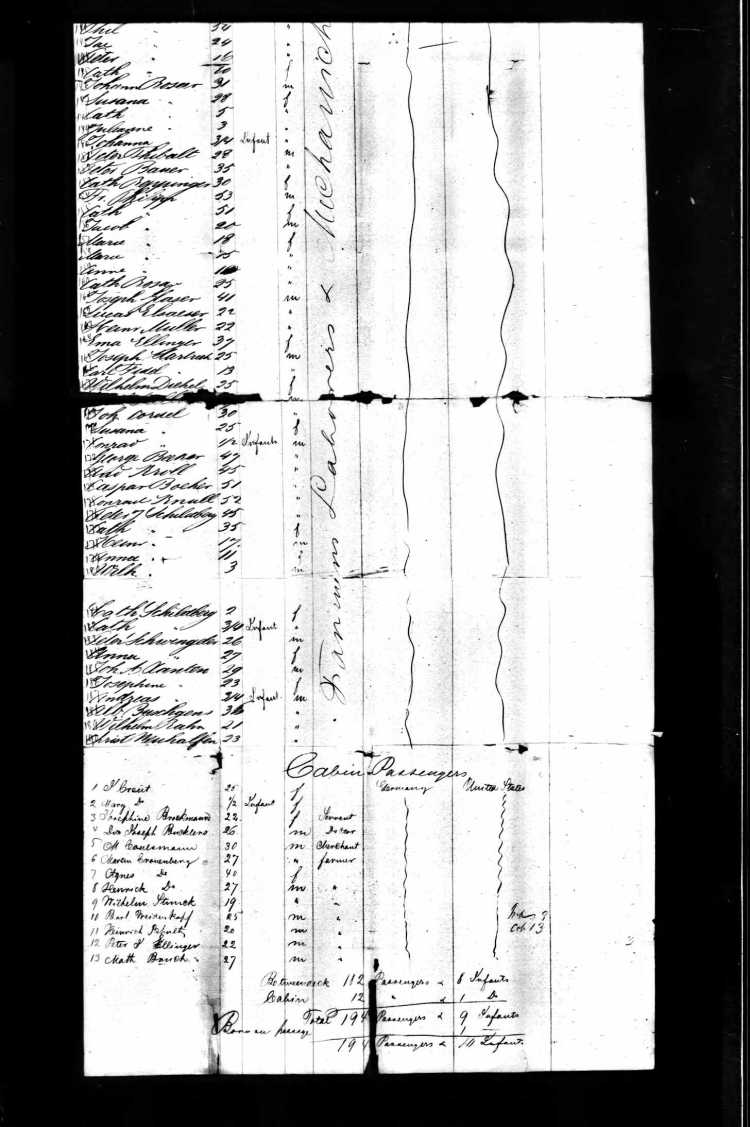

Into this small vessel were crammed 203 passengers, the crew, and all the supplies and provisions (including fresh water and livestock) required for a sea journey of up to two, or even three months.

There were, on departure, 190 between-decks (steerage) passengers, including eight infants, on the Hiero. The Phillips travelled in steerage.

Steerage, also referred to as “between-decks,” is the lower deck of a ship, where the cargo is stored above the closed hold. In the 19th century, steerage decks were used to provide the lowest cost and lowest class of travel, for European immigrants to North America.

In the early days of emigration, the ships used to convey the emigrants were originally built for carrying cargo. Temporary partitions were usually erected and used for the steerage accommodation. To get down to the between-deck the passengers often had to use ladders, and the passageway down between the hatches could be both narrow and steep. The way the ships were equipped could vary since there were no set standards for this. It was necessary that the furnishings could be easily removed, and not cost more than necessary. As soon as the ships had set their passengers on land, the furnishings were discarded, and the ship prepared for return cargo to Europe

The ceiling height of the between-deck was usually six to eight feet. Bunks, made of rough boards, were set up along both sides of the ship. The bunks were ordinarily positioned so the passengers lay in the direction of the ship, from fore to aft, but on a few ships the bunks were placed transversely or athwartships. The latter configuration caused passengers greater discomfort in rough seas. Larger ships might also have an additional row of bunks in the middle. On these ships there was only a small corridor between the bunks. Each bunk was intended to hold from three to six persons, and these were often called family bunks.

Steerage passengers slept, ate, and socialized in the same spaces. They brought their own bedding. Although food was provided, passengers had to cook it themselves. On rough crossings, steerage passengers often had little time in the fresh air on the upper deck. If passengers didn’t fill steerage, the space often held cargo.

Conditions varied from ship to ship, but steerage was normally crowded, dark, and damp. Limited sanitation and stormy seas often combined to make it dirty and foul-smelling, too. Rats, insects, and disease were common problems.

There were, on the Hiero, in addition to the steerage passengers, thirteen “cabin” passengers, including one infant. Herr Johann was well-to-do enough to be able to afford a “second class cabin” which included meals at the Captain’s table.

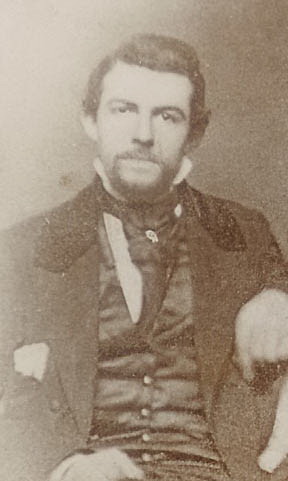

What follows is an account of the voyage of the Hiero. It is drawn from an English translation of the handwritten, German language journal of Herr Heinrich Johann that I received from a gentleman named Edwin Ellis, a great-grandson of Herr Johann. I am deeply grateful to Mr. Ellis for sharing his ancestor’s journal with me.

I have taken the liberty of lightly editing the journal entries to add a bit of clarity and improve the narrative flow. I have changed nothing of substance but have added some bits of historical information to certain events Herr Johann described, such as encountering the abandoned vessel Iris during the crossing.

Antwerp to New York – Approximately 4,000 Nautical Miles across the North Atlantic

En Route to America 1854 (From the journal of Herr Heinrich Johann)

Finally, after much effort and the difficulties of an overland trip with heavy baggage, crossing various borders, I arrived in Antwerp, and I am beginning the process of writing down the details of my journey, in part to serve as a reminder for myself in the future, and in part to better enlighten others, to the extent possible.

Thursday evening, 31-Aug-1854: In Dusseldorf I took leave from my friend Köttgen. I was supposed to arrive at the Prussian border on the Dusseldorf Railroad at Aachen, which I had hoped to cross that night. However, the start of the trip did not go entirely as planned, as the same train that brought me to Gladbach, through an unfortunate misunderstanding, took me back to Dusseldorf, and there was only a small room left in my first lodging quarters of the trip.

Friday, 01-Sep-1854: This morning at six with the first train in the morning I was supposed to go to Aachen, meet up with my luggage, and take another train to Antwerp. In Verviers, on the Belgian border, the official was rather gracious and assessed tax only on the lower end of the value range of my belongings at 5.50 Francs, without any further trouble of having to open anything for inspection. Yesterday evening I ate in Gladbach and had a cup of coffee and later, in Verviers, I had a half-pint of beer.

Without further ado upon my arrival in Antwerp at three o’clock in the afternoon, I looked up Agent Meyer from Elberfeld, and finally was able to arrange a second class cabin for 325.00 on the North America bound ship Hiero, leaving the next morning under the command of Captain Seabury, including meals at the table of the captain.

Day 1 – Saturday, 02-Sep-1854: Saturday morning early we boarded the ship. The wind was favorable, and there was no time to lose. With great anticipation I entered the room that was to be my abode for a long time, and we set sail. At eleven o’clock in the morning, Captain Seabury ordered the crew to cast off. We arrived in Vlissingen at eight o’clock in the evening.

Day 2 – Sunday, 03-Sep-1854: Sunday morning at 5 o’clock, we left Vlissingen with a favorable wind and headed out toward sea. At noon we passed Ostend. And by ten o’clock in the evening we passed Calais on our way toward Dover.

Day 3 – Monday 04-Sep-1854: Sunrise was at 5:48 o’clock according to my watch, by which time we were through the Channel. By day the weather was perfect with a favorable wind, but not blowing strongly.

Day 4 – Tuesday, 05-Sep-1854: Sailing along the English coast. There are constantly many sails in view and the trip was still a favorable one during the day. By that evening we were opposite Portsmouth. There was a calling out of the ship’s regulations by the ship’s fool, Buckley. At night there was a powerful storm. (n.b. I believe “Ship’s Fool” refers to the Second Mate)

Day 5 – Wednesday, 06-Sep-1854: In the morning we had a view of the Scilly Islands. This is the last land we shall see until America. Then there was a joyous singing of some German songs. In the afternoon we found the first fish (porpoise) in the area of the ship but we did not catch them. At night a strong wind and a strong tossing about with some people vomiting as a result.

Day 6 – Thursday, 07-Sep-1854: The whole day rather clear weather, yet only a slight wind that, toward evening, that pushed us quite a bit to the south.

Day 7 – Friday, 08-Sep-1854: Dreary weather, with the wind veering very much to the west, almost a crazy wind.

Day 8 – Saturday, 09-Sep-1854: Very bad weather. A strong wind toward evening that swelled up a storm. The seasickness – of the general sort. The first attack in my case came around two o’clock in the morning whereby my coat got ruined. There is general misery among the passengers with prayers being said on the steerage deck.

Day 9 – Sunday, 10-Sep-1854: Continued bad weather. No movement, and a miserable life on the ship. It is damp and dirty inside the ship, and outside it is pouring rain and there is a mighty tossing about.

Day 10 – Monday, 11-Sept-1854: Finally, after difficult days, we have a quiet moment. In the morning the wind was out of the northwest. We are moving very slowly forward. A little boy was born in the morning, around nine o’clock. Toward evening another storm came from the southwest.

Day 11 – Tuesday, 12-Sep-1854: The storm continued and grew in intensity throughout the day.

Day 12 – Wednesday, 13-Sep-1854: The storm that began on Monday evening reached its climax early this morning. Horrible life on the ship. Dirty. Loathsome. Terrible turmoil and tossing have made life miserable.

Day 13 – Thursday, 14-Sep-1854: Not until this morning did the weather get better. The sea became calmer, and the sails went up again. In the afternoon there was a whale near the ship. At night, another powerful storm.

Day 14 – Friday, 15-Sep-1854: Somewhat quieter in the morning. Yet soon it was again it became windier with the rain increasing in intensity, which in the night reached its climax and became truly dangerous. The ship is wet enough, even without the rain that you must bail water.

Day 15 – Saturday, 16-Sep-1854: At noon the weather is still unsettled and there is a greatly choppy sea. There is a strong southwest wind, but it is just quiet enough that the crewmen, who had not been able to do anything with our sails, were able to make some preparations again. Toward evening it became even more calm. Again, a little child is born.

Day 16 – Sunday 17-Sep-1854: On Sunday morning we were able to travel again for the first time. The wind was from the southwest and we went first toward the south, and then toward the northwest. At noon a ship came in sight which showed no foremast. Afterwards a rather lot of finished wood floated by. Toward evening again, a strong wind, but more calm in the night.

Day 17 – Monday, 18-Sep-1854: Dreary weather with west wind, afterwards there was a frost. The air became very still and there was no moving forward. Monday there were two other ships in sight. One had lost two masts and the other had lost one mast, a sign of mutilation from the previous storms.

Day 18 – Tuesday, 19-Sep-1854: Lovely weather with a somewhat northwesterly wind. For that reason, we went in a good direction. Very blessed. Tuesday afternoon we recovered several floating crates and refilled our supplies with their contents. Toward evening there was a completely calm sea and wonderfully calm weather. Slept very calmly at night.

Day 19 – Wednesday, 20-Sep-1854: Lovely wind at noon, good sailing. Full sails, the wind behind us, somewhat in the east, also a little to eat.

Day 20 – Thursday 21-Sep-1854: The morning was a beautifully lovely morning. The sea totally calm. Neglected indeed to note that the morale had improved tremendously on the ship; people’s appetites had been better than before – but otherwise life on ship is very boring.

No wind the entire day and the calmness only increasing, the sea like a meadowland, and lovely weather in the afternoon. And then finally a whale neared the vicinity of the ship and entertained us with his moving about and spraying out water. After sunset there finally was a fresh southeast wind which lasted the entire night and led us farther on our journey.

Day 21 – Friday, 22-Sep-1854: In the morning a south wind. Smooth sailing. Toward evening the wind became somewhat too strong, for which reason several sails had to again be pulled in. At night again, a horrible tossing about.

Day 22 – Saturday, 23-Sep-1854: The whole day dreary, rainy weather. The wind at first favorable. Afternoon totally calm. Evening totally gentle wind.

Day 23 – Sunday, 24-Sep-1854: In the morning foggy with a south wind. Afternoon clear with steadily increasing wind, which at night brought in a formidable storm.

Day 24 – Monday, 25 September. A very choppy sea and a very powerful wind. The sails had to remain pulled in.

Day 25 – Tuesday, 26-Sep-1854: At four o’clock in the morning was there a good northeast wind and good sailing until the evening, then uncertain breezes and a standstill. At night wind to the south. –

Day 26 – Wednesday, 27-Sep-1854: For several days there have been no swells and we have seen a few more birds. In the morning, in southerly direction, there was a ship in view. The wind until noon was favorable, afterwards it became too strong, and toward evening it was a weak and unsustained wind from the northeast.

Day 27 – Thursday, 28-Sep-1854: In the morning there was a southeast wind. At night the wind shifted toward the south and made for very quick sailing in the best direction. There are several ships in view that we are overtaking.

Day 28 – Friday, 29-Sep-1854: In the morning there was a continual, powerful southwest wind, making for very choppy seas. Before noon we overtook a three-mast ship. Towards evening the weather became calmer, and at night it was entirely calm. There was an Incident of theft on the ship.

Day 29 – Saturday, 30-Sep-1854: South wind and then calm. Toward evening east wind, very fast movement. Then a storm and quite horrible tossing. At night near the banks of Newfoundland.

Day 30 – Sunday 1-Oct-1854: Quite foggy, nasty day. Totally calm, but horrible tossing – very unpleasant.

Day 31 – Monday, 2-Oct-1854: At night the first newborn child died. After breakfast he was buried at sea (i.e., thrown into the water). Until 12 o’clock noon there was fast sailing to the southwest, then too strong a wind, and afterwards a horrible storm, during which we were thrown off our target. At night not calm.

Day 32 – Tuesday, 3-Oct-1854: South wind from early to evening pushing toward the west, continually improving weather. Evening clear and clear. Still on the banks of Newfoundland.

Day 33 – Wednesday, 4-Oct-1854: Very clear the entire day, and calm. In the morning a bunch of sea lions (400 of them) very near to the ship on the calm ocean. Also ducks on the “fishpond.” After sunset a fresh breeze from the southeast. At night calm and rather quick sailing. –

Day 34 – Thursday, 5-Oct-1854: Still moving nicely forward. A lot of fog on the banks. At eleven o’clock we caught up with a ship that had come into view early evening. Until the night we were under a shroud of thick fog, racing forward, the wind to the northwest.

Day 35 – Friday, 6-Oct-1854: Wind from the Northwest and our direction is to the south. Lovely weather. At night the wind from the south, and our direction is to the northwest.

Day 36 – Saturday, 7-Oct-1854: Eleven o’clock in the morning. For one hour a ship has been in view toward the south, without masts and without direction. Our ship is moving closer in order to check up on it.

One o’clock in the afternoon. The ship is the Iris out of London. The main mast is splintered and is hanging to one side. The ship seems to still be new but has suffered tremendous damage. Unfortunately, the captain did not concern himself any more with it after he had convinced himself that there were no more passengers aboard.

The barque Iris was abandoned in the Atlantic Ocean after severe storm damage. Her crew were rescued by the brig Magnet (United Kingdom). Iris was on a voyage from Wallace, Nova Scotia, British North America to London.

Day 37 – Sunday, 8 October. Until this morning at 4 o’clock SW wind direction NW, then lovely NW with direction to the SW which helps the goal of covering the remaining 850 nautical miles, hopefully in a few more days. The weather clear, and in the morning, there were three fishing boats in view. All the passengers talked a lot.

On Sunday afternoon, we saw many fishing boats near our ship, and also saw a small whale for a moment. In the evening there was an east wind, but it was too calm to make much headway. We moved slowly at night.

Day 38 – Monday, 9-Oct-1854: Since about noon the wind again became strong enough for sailing. A little, long-beaked bird alighted on the ship. We travelled well today, making perhaps 600 nautical miles.

Day 39 – Tuesday, 10-Oct-1854: In the morning the wind came from the south, a strong one that grew into a storm. Three sailors and the ship’s helmsman, Allen, have taken ill. Two falcons landed on the ship, a sign that land is near. Wind changed to northwest. Toward noon it became calmer, but still with very high seas and horrible tossing. Toward evening it became entirely calm, and at night we were standing still.

Day 40 – Wednesday, 11-Oct-1854: A very wonderful morning. Looked at the sunrise from the mast. The sea a mirror. Seven, and then later nine, ships in view. Toward eight o’clock a slight southerly wind. The whole day lovely, warm weather, a good autumn.

Day 41 – Thursday, 12-Oct-1854: This past night a truly beautiful sunset and sunrise. Up until now (10 o’clock) we had a strong southerly wind. We saw a steamship. The wind ‘til evening strong, also due to strong fog cover a high sea, no storm to fear.

Day 42 – Friday, 13-Oct-1854: Last night became calm. This morning at 7 o’clock we spied the American coast, perhaps Maine. A northerly wind, cold but very favorable. We sailed peacefully the whole day.

Day 43 – Saturday, 14-Oct-1854: Early Saturday morning saw lots of ships with lanterns. Wind from the south and southwest. In the morning we caught a duck. The whole day no sailing. In the evening fog, and at night a little stormy. Electric light on the front mast. Slaughtered a pig.

Day 45 – Sunday, 15-Oct-1854: High seas. The storm is one day past and gives us the expectation of staying at sea for another day. At 7 o’clock the first land, but unfortunately not near New York. Perhaps Block Island. In the direction to the north. At noon caught sight of New York – lovely view available to us continually between Newport and Block Island. Sunday evening a lovely sea.

Day 46 – Monday, 16-Oct-1854: Still between Block Island and Newport, and Newport and Block Island.

Day 47 – Tuesday, 17-Oct-1854: This past night we finally got out farther into the sea, but in the morning totally no wind. Numerous whales near the ship, captured two little dolphins. In the evening at four o’clock, a fresh breeze from southwest.

Day 49 – Thursday, 19-Oct-1854: Arrival in New York.

On Saturday 21-Oct-1854 I wrote to mother and to Köttgen.

END OF JOURNAL

Herr Johann, who apparently Americanized his given name to Henry, eventually ended up in West Point, Mississippi working as a jeweler.

The Phillips eventually made their way to Scranton, Pennsylvania and it’s environs.